Contrary to popular belief, mainly brought about by scary shark movies, you have more chance of being killed by a coconut than a shark! Over-fishing and unsustainable practices are causing shark populations to decline worldwide. Amazing sharks play an important role in our oceans and on our majestic reefs and we should all be concerned about their numbers declining. We believe that the big danger is not sharks; the big danger is shark extinction. Here in Australia, we are luck to have bountiful species of shark living off our coastline. Read on to discover some interesting facts about sharks of Australia, why we need sharks in Australia and why we need to protect sharks living off the coast of Australia in our Amazing Australian Shark Facts blog…

Sharks in Australian Waters

There are considered to be around 180 species of sharks in Australian waters and 500 species worldwide. In fact, around 50 species of shark live right here, off the Eastern Coast of Queensland. Eastern Australia’s grey nurse sharks are considered critically endangered and school sharks (sometimes known as flake in fish and chip shops) and scalloped hammerheads are on the endangered shark list too.

Sharks Commonly Found off Australia

The following sharks are commonly found off Australia’s coast: Great White, Port Jackson, Thresher, Zebra Shark, Tiger Shark, Tasselled Wobbegong, Whale Shark, Oceanic Whitetip, Blacktip Reef, Grey Nurse, Bull Shark, Bronze Whaler, Great Hammerhead, Blind Shark, Pygmy Shark

Why Do We Need Sharks?

Why Do We Need Sharks?

There is no doubt that we need sharks. As apex predators, sharks help maintain the balance of life in the sea. Sharks are a vital part of the food chain, controlling mid-sized predators and allowing small reef fish to thrive. Small reef fish take care of our amazing coral reef, therefore sharks help keep coral reef healthy. Without sharks, we would be denied the pleasure of exploring amazing underwater habitats such as the world’s largest natural wonder, Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef. The global economic impact on tourism and of declining fish stocks would be huge. So, have no doubt, we need sharks!

Why Are Shark Populations in Decline?

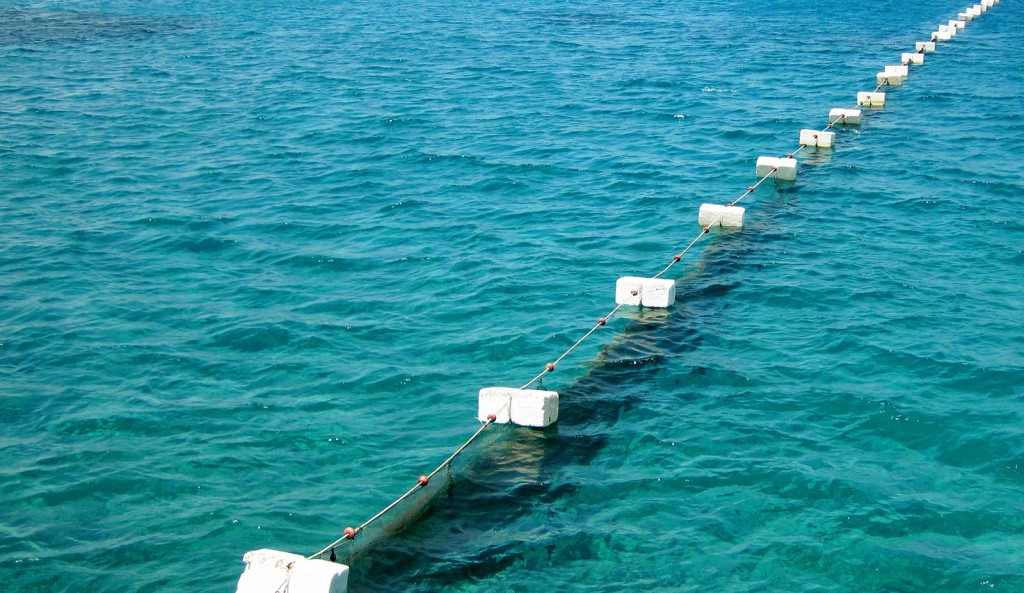

Shark populations are in decline globally and in Australian waters. 100 million sharks are killed in worldwide fisheries each year and habitat degradation, pollution and climate change are also impacting international shark populations. Controversial shark nets and drum lines (designed to protect human populations) add further to the decline.

Sharks live a long time (20-30 years), grow slowly and take a long time to mature and reach reproductive age. This means that even if we slow the decline in shark populations now, populations will take a long time to recover.

Should I Be Scared of Sharks in Australia?

Should I Be Scared of Sharks in Australia?

No! We don’t think you should be scared of sharks. The ocean is their home and when we visit their home we need to be very aware and respectful of them.

- On average, one person a year is killed in a shark attack in Australia.

To put things in perspective…

- 5 people die from falling out of bed

- 10 people are struck down by lightning

- 1,100 are killed on our roads

Ultimate Shark Facts

Check out our ultimate shark facts and discover how much you really know about sharks.

- The largest species of shark is the whale shark

- Baby sharks are called pups

- Shark bones are made of cartilage

- Many sharks have multiple rows of sharp teeth – they can grow 35, 000 in a lifetime

- Shark skin feels like sandpaper

- The collective noun for a shark is a Shiver (or School, Shoal)

- The fastest shark in the ocean is the Shortfin Mako Shark (up to 74k an hour)

- The smallest species of shark is the Dwarf Lantern Shark (smaller than a human hand)

- Sharks have eyelids but they do not blink

- Sharks do not see in colour

- 10% of shark species are bioluminescent – they light up in the dark

- 180 species of shark live off the coast of Australia – 400 species worldwide

- Bull sharks can live in fresh and salt water

- Some sharks lay eggs (oviparous) others give birth to live young (viviparous), and some are a combination of these two, they start life inside their mother as an egg, hatch inside her and then are born live (ovoviviparous)

- Egg laying sharks lay egg cases known as mermaid’s purses

- Unlike humans, sharks breathe through gills, so their nostrils are purely dedicated to smelling

- Sharks are able to detect blood from 5 km

- Sharks can identify which of their two nostrils have picked up a scent – enabling them to determine the direction to swim to find food

- Some species of shark can survive for up to 3 months between meals

- Sharks can sense vibrations from 3 kilometres away

What Can I Do to Help Protect Sharks?

- Educate yourself and your friends

- Share your love of sharks on your social media channels

- Join a volunteer shark conservation organisation like sharkconservationorg.au, marineconservation.org.au, seashepherd.com.au (make a donation if you can)

- Join a beach clean or just clean as you go!

- Buy sustainable seafood and check restaurants have done so. Avoid flake at the Fish & Chip shop as it may be endangered shark

- Ask politicians to support ocean acidification research

Ocean Life Education is passionate about protecting all marine animals and focusing on the important role sharks play in our oceans. We aim to separate fact from fiction when it comes to the most feared fish in the sea.

Check out our Shark Discovery Program for more information on how to inspire kids to love and respect sharks: www.oceanlifeeducation.com.au/programs/holiday-program/

Want to know more about Amazing Australian Shark Facts?

Check out our Amazing Sharks Online Course