We Aussies love our beaches – in the warmer months the coastline has a magnetic pull, drawing us to the sand, sea and surf in our thousands.

But while the thought of a refreshing ocean dip might be appealing, the concept of potentially coming face to face with one of our most feared predators has prompted officials to take drastic action.

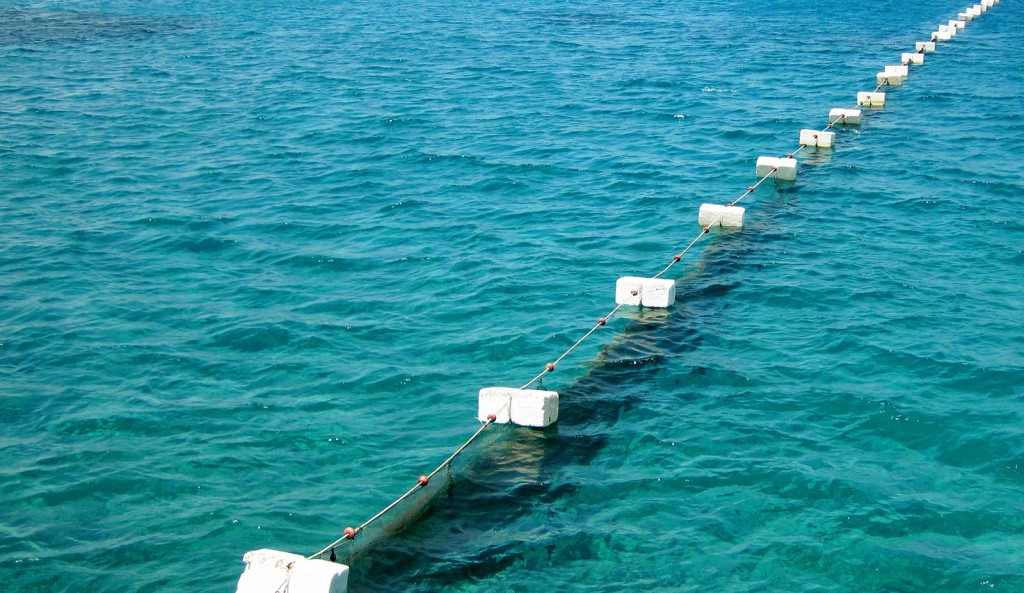

Shark nets have been deployed off the shoreline of the east coast for more than 80 years. But they offer a false sense of security. Stretching less than 200 metres long and extending down only 6 metres, these mesh barriers are at best a deterrent and certainly don’t make beaches attack proof.

Sharks can get under, over or around them, and as it turns out, more are caught on the shore side of the net when they’re heading back out to sea, than when they’re swimming towards shore.

The holes in the mesh are around 50 centimetres across – large enough to let small animals pass through, but the perfect size for trapping bigger species.

Turtles, dolphins and rays are common victims of the nets – becoming entangled and drowning or starving to death. A major concern is the ensnaring of humpback whales on their journey back to Antarctica after their annual breeding season in the tropics.

Calves in particular are easy prey – in just over a decade 55 have been caught in the shark nets, including one off Noosa in late September this year. Another swam down to Sydney with the remnants of a Queensland net still wrapped around its mouth.

But the toll on the animals targeted by these barriers is far greater. In 2017 alone, more than 500 sharks were caught in the nets off Queensland – 377 died, more than 100 others had to be euthanised – only 20 were released.

Amongst the victims were grey nurse sharks which are classified as critically endangered and pose no real threat to us. The vast majority of species share the sea quite peacefully with people – only a handful of sharks are responsible for fatal attacks on humans.

Just to put it all into perspective, on average one person a year is killed by a shark in Australia, as opposed to 5 dying from falling out of bed, 10 struck down by lightning or perhaps the most sobering, more than 1,100 taken on our roads.

Shark attacks are extremely rare and there is no scientific evidence to prove that nets protect humans. What we do know is the attempt to keep us safe is killing marine life indiscriminately.

Removing so many animals, including apex predators, will have an impact on local marine ecosystems – but we won’t be able to calculate that cost until far too late.

Marine biologist, Holly Richmond, feels so passionately about the need to remove all nets, she’s created a video: www.thesharknetfilm.com

Ocean Life Education is passionate about protecting all marine animals and focusing on the important role sharks play in our oceans. For more information about our programs including our Shark Discovery presentation visit: https://www.oceanlifeeducation.com.au/programs/

They are possibly the most misunderstood of all the sea creatures – apex predators capable of inspiring both fear and fascination in equal measure. But far from being the killing machines portrayed in the movies, most sharks are more at risk from us than we are from them.

They are possibly the most misunderstood of all the sea creatures – apex predators capable of inspiring both fear and fascination in equal measure. But far from being the killing machines portrayed in the movies, most sharks are more at risk from us than we are from them.